History Café serves up a century of stories on the Black Mountain Public Library

Tom Stiles shares tale of humble beginnings and overwhelming support

Fred McCormick

The Valley Echo

July 25, 2022

Tom Stiles is presented with a certificate of appreciation and a wooden outline of mountains following his July 18 presentation on the 100-year history of the Black Mountain-Tyson Public Library. Photo by Fred McCormick

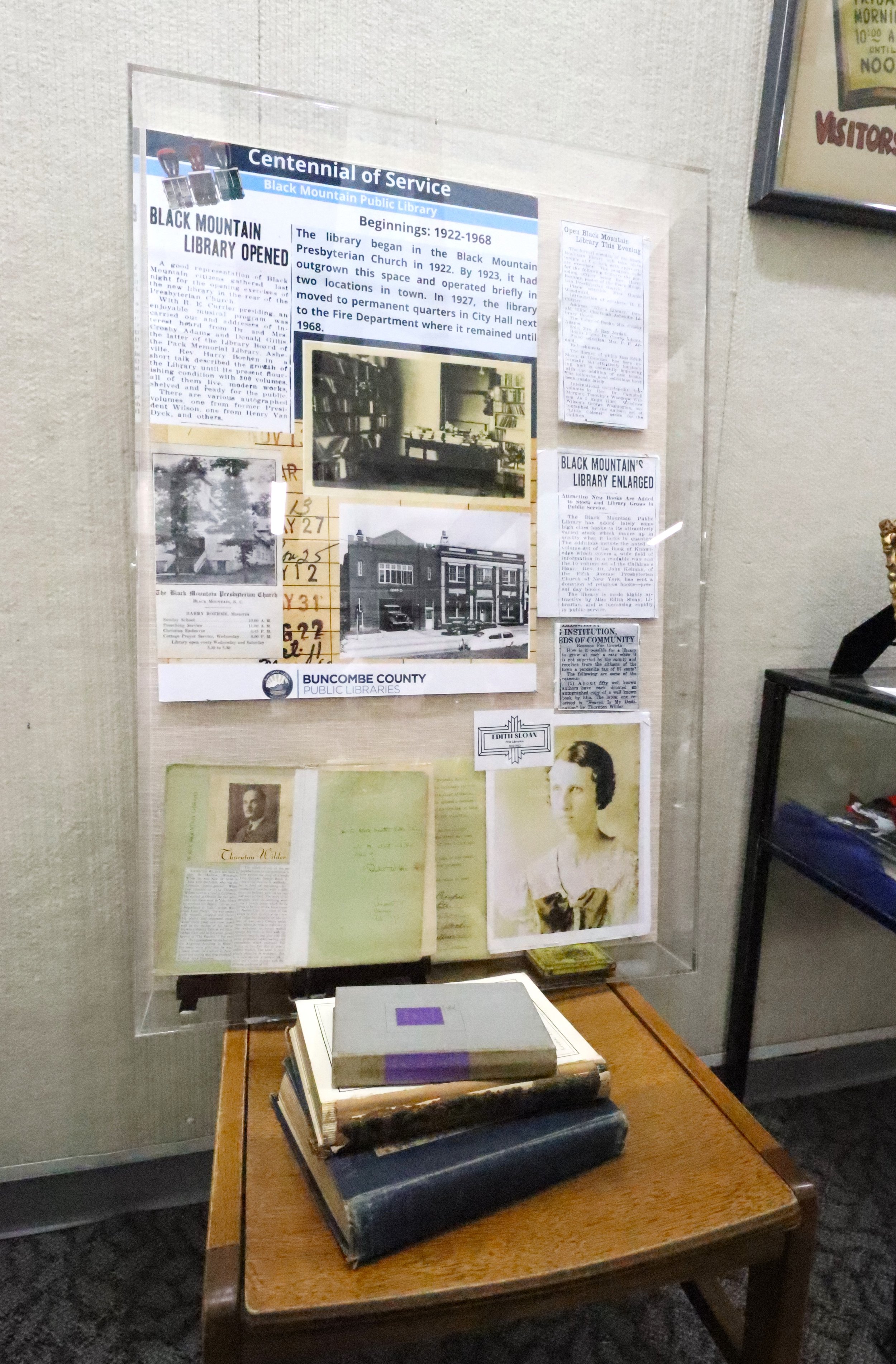

In July of 1922, when Black Mountain itself was not even 30 years old, forward-thinking residents of the burgeoning town recognized the value of access to knowledge and information. Fifty books were donated and stored in a small classroom inside the Black Mountain Presbyterian Church, and a beloved community institution was formed.

A century later, on July 18, supporters of the Black Mountain Public Library gathered in its community room for the latest in the 2022 History Café series, organized by the Swannanoa Valley Museum, as Tom Stiles presented a historical narrative recounting the humble beginnings and the community’s continuous support of its local library.

The event, a collaboration between the museum and library, celebrated one of many milestones in the 100-year history of the branch, which was established in the original Black Mountain Presbyterian building that once stood in the church's present day parking lot.

“The Rev. Harry Boehme, pastor of the church, served as the first administrator. Ms. Edith Sloan volunteered to be the first librarian,” said Stiles, a historian and member of the Friends of the Black Mountain Library who began researching the topic in 2018. “The library was open four hours a week.”

While the first few months allowed volunteers to establish the library, the community formally welcomed it that fall.

“As was the case with organizations opening 100 years ago, the program was formal, with music presentations and refreshments,” Stiles said. “The library was very popular and grew rapidly.”

In less than a year, the library’s collection would grow from a few dozen books to more than 1,000 volumes, and a board of trustees was established to oversee the operation. Under new leadership, the growing library was moved to two rooms over a new post office building on the east side of Cherry Street.

Early funding for the local library came from citizens and visitors, according to Stiles.

“This included some of the most distinguished people in America,” he said. “Among them were Rodman Wanamaker, a patron of the arts and sciences; William Jennings Bryant, who lived in Asheville from 1917 to 1920 and former President Woodrow Wilson, a southerner who attended Davidson College.”

Residents of Black Mountain, however, would express their overwhelming support for the library at the polls.

“A taxation of 6 cents per $100 of valuation, supporting the library, was an issue in the municipal election of May 5, 1925,” Stiles said, sharing a slide of the town’s official count from the referendum. “The official count for library support: 166, and against it: 11.”

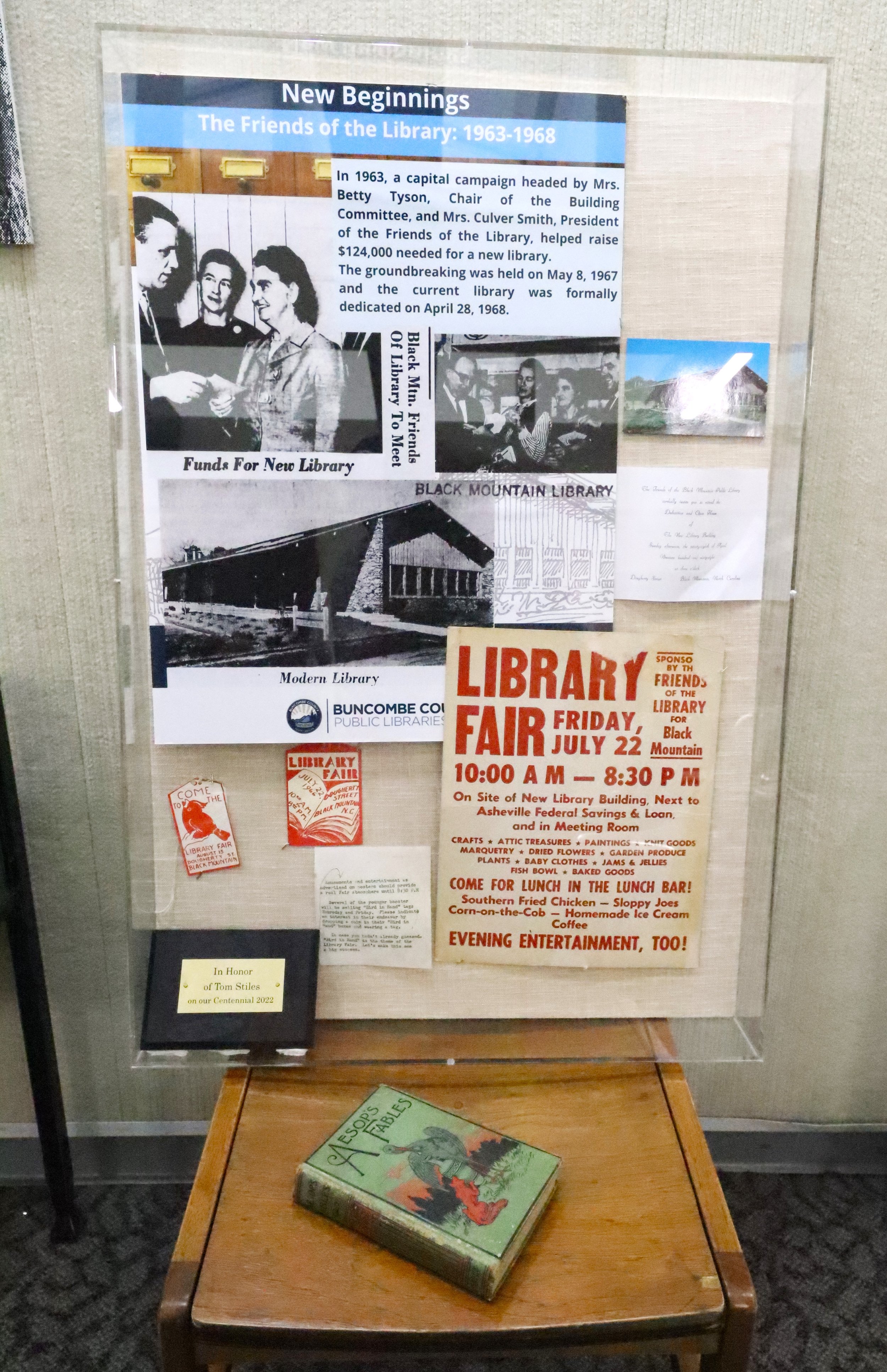

A display in the education room of the Black Mountain Library containing the scissors used in the 1968 ribbon-cutting ceremony opening the new facility and a photo of Betty Tyson is among several historical artifacts exhibited in recognition of the branch’s 100th anniversary. Photo by Fred McCormick

Within its first three years of existence, the collection of books had grown to 2,700, and the community’s willingness to fund the library allowed the town to move into a space above the former town hall, on West State Street.

“But, the library was not for everyone,” Stiles said. “Racial segregation was enforced throughout the country.”

The presenter cited a 2003 article from The Black Mountain News, which included an interview with Inez Daugherty, an African-American native of the town.

“Just four years before she died, we learn of her experiences with the library,” Stiles said, recounting Daugherty’s story. The article described Daugherty, who was born in 1912, as an “avid reader,” who as a young woman asked a white friend to check out books for her.

When the library moved to town hall, Daugherty was turned away when she attempted to access books from the collection. Libraries throughout the region would remain segregated until 1962. One year later, the continuously growing demand for services created a drumbeat within the community that shaped the course of the library’s future.

Stiles shared a story told by Betty Tyson, who was interviewed for the book, “A History of Black Mountain and its People,” written by Joyce Justus Parris and published in 1992, ahead of the town’s centennial anniversary the following year. Betty and her husband, Alfred “Bub” Tyson who opened Tyson Furniture together in 1946, would become key figures in the fundraising efforts for a new library building.

“With the increase of patrons came the realization that using the library was difficult and inconvenient for many,” read an excerpt of Betty's recounting of the library’s history, as shared by Stiles. “The steep stairs were a hardship for many older people, and a danger for the very young.”

The Black Mountain Library, which began with a collection of 50 books in a classroom inside the Black Mountain Presbyterian Church, is celebrating 100 years in 2022. Photo by Fred McCormick

Residents of the town once again rallied in support of the library, as 135 people joined the Friends of the Black Mountain Library, shortly after its formation in 1963. Membership would balloon to over 400 two years later, as the library’s board of trustees voted to join the Buncombe County system.

Led by Betty, who served as the president of the FOL, Black Mountain elected officials designated the organization the town’s agent to solicit funding and plan construction for the construction of the $124,000 building. The nonprofit opened the White Donkey thrift store on East State Street to benefit the library.

Efforts to find a suitable location for the modern facility were boosted by the involvement of Willis D. Weatherford, founder of the YMCA Blue Ridge Assembly and resident of the town, according to Stiles. Wilma Dykeman provided an account of Weatherford’s role in negotiating the acquisition of property on North Dougherty Street in her 1966 book, “Prophet of Plenty: The First Ninety Years of W.D. Weatherford.”

The library committee identified the lot, adjacent to the Asheville Federal Savings and Loan Association, as an “ideal location.” The bank, which would become Asheville Savings Bank until it was acquired by First Bank in 2018, offered to donate a 7,700-square-foot parcel for the construction of the facility.

“Weatherford politely declined,” Stiles said. “It did not allow enough room for spaciousness, or subsequent growth.”

The bank then proposed a 12,800-square-foot piece of land for the project, in honor of the bank’s first chairman, Charles Parker, and the FOL accepted. The town purchased the remainder of the property.

The 4,000-square-foot structure was designed by Anthony Lord, the architect whose work in the region includes The Asheville Citizen Times building and multiple projects on college campuses in Western North Carolina.

While the majority of the funding for the construction was available through federal and regional programs, the FOL needed to raise $45,000 in the community. The organization hosted local events, including book reviews, discussions and a variety of fundraising initiatives.

“More than 400 individuals and businesses gave money towards the building,” Stiles said. “No single donation was over $3,000.”

Dozens of members of the Friends of the Black Mountain Library attend Tom Stiles’ presentation on the 100-year history of the branch. Photo by Fred McCormick

Betty, whose tireless advocacy for the new library played a key role in building momentum for the project, turned over the first shovel of dirt when construction began in May of 1967. She was joined by other supporters of the library, including Weatherford.

“Dr. Weatherford asked that all remember that ignorance is a disease,” Stiles said. “One that a new library will play an important role in curing.”

The modern library opened its doors on March 10, 1968.

“The move from town hall, of approximately 12,000 books, card files, desks and supplies, was accomplished in just four hours,” Stiles said. “The books were actually moved by members of the FOL, Boy Scout and Girl Scout troops and teenage members of the Red Coach Coffee House.”

Joe Tyson, the son of Bub and Betty who assumed control of the family business with his wife Carol in 1974, transported the collection in a Tyson Furniture truck. Joe and Carol were among those in attendance at the centennial presentation.

In its new home, the library would become a meeting place for residents and community organizations. Additional space was added in 1981, with the completion of the education room on the east side of the building.

The library was officially renamed the Alfred Forbes and Mary Elizabeth Tyson Library in 1994, recognizing the couple’s efforts to rally community support for the facility. While her husband Bub had passed in the years prior to the re-dedication, Betty called the building “a wonderful place to open up the world to readers.”

Then-mayor Carl Bartlett, in a series of quotes shared by Stiles, lauded the foresight of the Tysons, calling the library a “cathedral of learning” with the ability to change the lives of those who enter it.

Local support for the library remained consistent in the years that followed, with the addition of a Seed Lending Library, a chimney swift tower and a wide range of programs. However, residents would again rally around what had become a community center by 2021, when a report presented to the Buncombe County Public Library system recommended, among other things, closing the Black Mountain branch and combining it with the Swannanoa Library in a regional facility.

A panel recounting a Centennial of Service of the Black Mountain Public Library is among the items displayed in the education room. Photo by Fred McCormick

A listening session held by the county library advisory board in Black Mountain was attended by more than 100 people.

“Most residents advocated keeping the library here, in the heart of Black Mountain and accessible to all,” Stiles said. “The Friends gathered over 900 signatures on a petition opposing the move.”

County commissioners, in response to the feedback from the community, suspended the proposal in June of 2021.

The speaker closed his presentation with a video, produced by SkyShots Aerial Photography, depicting the sites of all four locations of the library. The drone footage began in the parking lot of the Presbyterian church, before traveling south to Cherry Street, back up to State Street and ending at the current location on North Dougherty Street.

“It took 100 years to travel about four blocks,” Stiles said.

Last year, under the leadership of Branch Manger Melisa Pressley, the 13th person to hold the position in the library’s history, nearly 87,000 items were circulated by the branch, while its collection of books has grown to more than 25,000.

“The Black Mountain Library continues to be the heart of this community,” Stiles said.