A Legacy of Labor and Leadership

From slavery to Town Hall

Fred McCormick

The Valley Echo

January 11, 2021

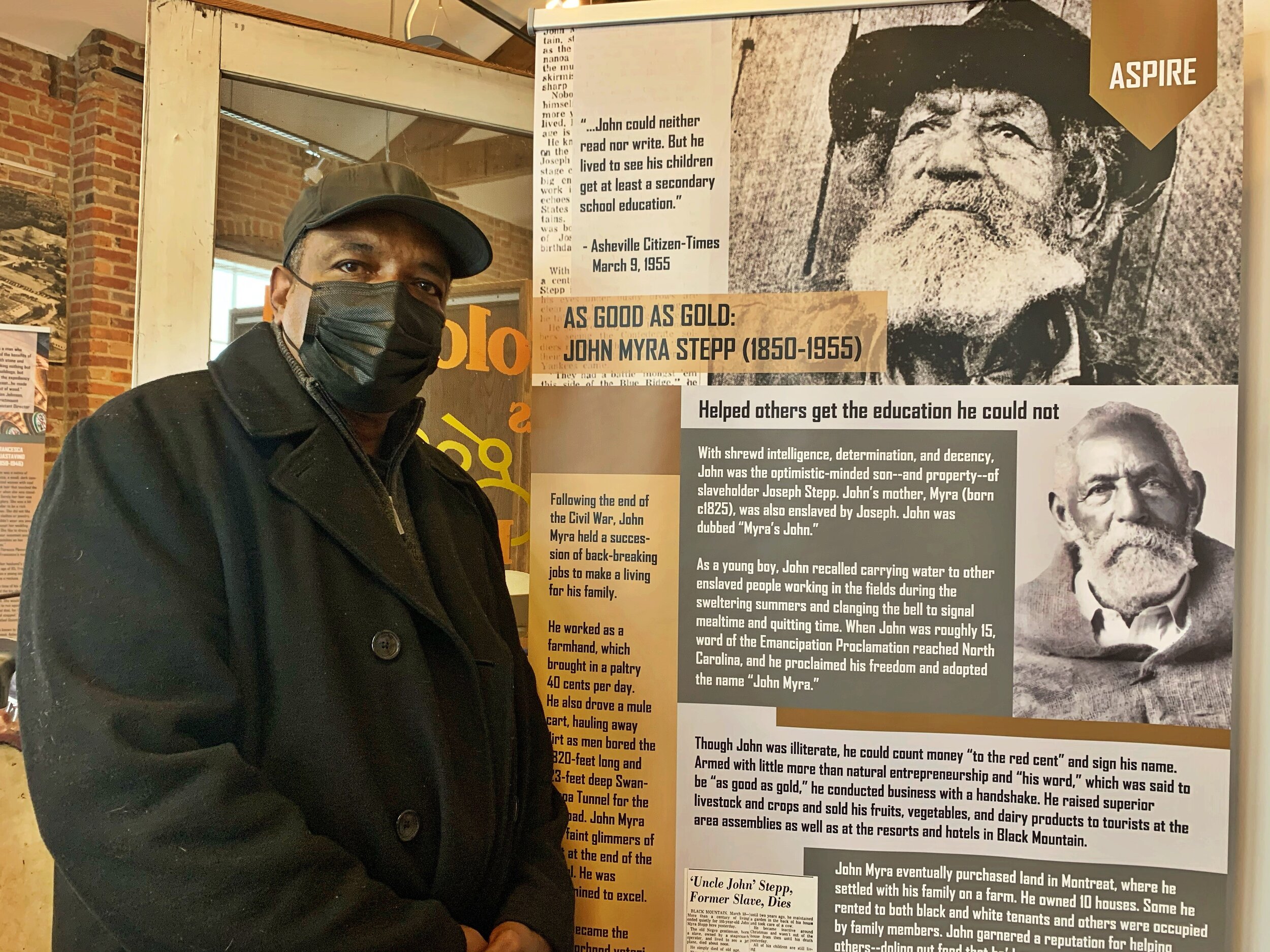

Black Mountain Alderman Archie Pertiller, Jr. is the great-grandson of John Myra Stepp (1850-1955), who is recognized in the Swannanoa Valley Museum & History Center for his lifetime of achievements, including overcoming slavery to fund the town’s first African-American school and becoming a successful businessman. Photo by Fred McCormick

There was an air of stoicism surrounding Archie Pertiller, Jr. as he rested his left hand on the Bible and raised his right arm, Dec. 14, in the boardroom of the Black Mountain Town Hall. The calm, confident demeanor with which he took the oath to uphold and protect the laws of his hometown was long familiar to those closest to him, and played a key role in earning him more votes than any candidate in the history of the town.

Many of the more than 2,600 residents who elected Pertiller that witnessed the moment on a livestream of the regular monthly meeting were likely unaware of its historical significance, but it was set in motion nearly two centuries ago by a man born into slavery just miles away.

John Myra Stepp was born in Grey Eagle, now Black Mountain, in 1850. Known as “Myra’s John” at birth, he was the son of an enslaved woman, Myra, and the man who claimed her as his property, Joseph Stepp. While born into the institution, labeling John Myra a “slave” would paint an incomplete picture of his 105-year life and the legacy that endures today.

One of many offspring of Joseph and the women he held in captivity, John Myra spent his childhood carrying water to other enslaved people working in the fields of the Swannanoa Valley. He was around 15 years old when his family received word of their freedom, roughly three years after Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Already known for his optimistic and caring demeanor, Myra’s John became John Myra when he began a life free to pursue a brighter future for those who came after him.

Among those many descendants is his great-grandson, Pertiller, who still lives in a home in the area of Black Mountain known as Brookside to the African-American community that developed around the land John Myra would go on to acquire. The alderman grew up in the home in which his great-grandfather died peacefully in 1955, just a year before Pertiller was born.

“He was my father’s grandfather, the father of my grandmother,” Pertiller said. “When he passed, my father acquired the home he lived in.”

The property is only a small portion of what was once John Myra’s land, which sits just west of present-day Flat Creek Road. Pertiller’s mother lives in the home now, and his house is “just below.”

A Legacy of Community

Archie Pertiller, Jr. who received more votes than any alderman candidate in the history of Black Mountain, grew up in a home built by his great-grandfather. John Myra Stepp was born into slavery and acquired a significant amount of land in what would become the Brookside community in the years that followed. Photo by Fred McCormick

John Myra lies eternally at rest in the Oak Grove Cemetery in the Cragmont community of Black Mountain. The land is the site of the historic Thomas Chapel A.M.E. Zion Church, built in 1922 by the descendants of men and women recently freed from slavery. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, it was constructed to replace Tom’s Chapel, which was built around 1892.

The property upon which the original church once stood was donated to the “Trustees of the Colored Church known as Tom’s Chapel” by John Myra’s sister Martha to be used in perpetuity “as a place of Divine worship for the use of the ministry and membership of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in America,” according to the Registry. It was the center of the African-American community for many years and was one of several Black churches that helped maintain the strong family bonds between Cragmont and Brookside.

“Back in those days, your church was the center of your community,” Pertiller said. “In Brookside there were two (African-American) churches and two in Cragmont. We were all family, and we would all see each other on Sundays.”

The Brookside neighborhood of Pertiller’s childhood does not look like it did when he was young, and even less like it did when John Myra bought the undeveloped land in what was considered the Montreat community at the time. Since being granted his freedom John Myra had worked as a veterinarian, farmer, mule cart operator for the railroad tunnels being blasted through the Swannanoa Gap and acquired, and later sold, 40 acres of land near present-day Black Mountain Center and Grove Stone quarry.

John Myra subdivided the property on what would become the Brookside community, and sold many of the plats of land. His family would settle on a farm there and he constructed 10 houses on the land he retained. He was known to rent to tenants of any race and reportedly worked with those who struggled to cover the expense.

Much of the story of John Myra’s life was handed down directly to Regina Lynch-Hudson from his daughters — Bessie Stepp Pertiller (1908-2006) and Minnie Stepp Whittington (1915-2005). Pertiller is the grandmother of Archie and Whittington the grandmother of Lynch-Hudson. The decades of research of the semi-retired publicist and passionate family history preservationist on her great-grandfather also includes interviews with Zepplyn Stepp Humphrey (1914-2014), the granddaughter of John Myra. “There were no greater authorities on John Myra’s life and legacy than these three women,” said Lynch-Hudson.

Lynch-Hudson collaborated with the Swannanoa Valley Museum & History Center to produce both in-person and online exhibits sharing the story of John Myra, but the work of preserving that heritage has long been a priority for the family. A tangible example of those efforts, a yellowed clipping of a 1954 issue of the Asheville Citizen-Times, is one of Lynch-Hudson’s earliest memories of her great-grandfather.

The article, written by Phillip Clark and published when John Myra was 104 years old, maintaining a strong voice and clear eyes, was a treasured piece of family history, according to Lynch-Hudson.

“I would take the clipping out and marvel at it as a little girl,” she said. “A big part of what makes that article important today, is that it was researched and written while he was still alive. It was in-depth, and the information was so powerful. The fact that in 1954, a Black man would’ve received such a glowing and lengthy write-up in the Asheville paper, shows what a respected person John Myra Stepp was.”

Pertiller was born only one year after the death of his great-grandfather, and in many ways it was as though he knew him. The stone foundation on which his childhood home sits was built by John Myra.

“I was always told that he was hard-working, and that helped me understand why so many people in our family were such hard workers,” he said. “That’s how my family has always been, we push ourselves hard.”

As a teenager, Pertiller began to fully comprehend the impact of his great-grandfather when he would step out of his yard onto John Myra Avenue, where he lives today.

“He was an incredible man and so well-respected in the Valley,” he said, walking along the street his great-grandfather used to call home. “His mother was a slave, his father a slave-owner and he goes on to teach himself to be a veterinarian, sell the vegetables he grew on his farm to Black and White people and put himself in a position to acquire this land.

“It really gave so many of us this sense of family pride in our history,” he continued. “For me, his story helped shape how I viewed the world. With my great-grandfather being biracial, I never really saw color growing up. People were people, and how can I dislike a person based on being a different race when, since the very beginning, that’s what my family looked like?”

A Legacy of Education

Archie Pertiller, Jr. stands at the corner of East Street and John Myra Avenue, which was named for his great-grandfather John Myra Stepp. The intersection is blocks away from where Stepp purchased land to build the Flat Creek Road School, the first for African-American children in Black Mountain, only two decades after he was emancipated from slavery. Photo by Fred McCormick

John Myra could “count money to the red cent” and conducted honest business with a handshake, according to family history, but growing up in slavery prevented him from receiving a formal education. While hard work and determination were his tools for success, he wanted to equip future generations with more.

“Obviously, he was a talented entrepreneur and worked very hard to earn enough money to survive, and then save,” said Swannanoa Valley Museum & History Center Executive Director LeAnne Johnson. “But perhaps his biggest accomplishment was that he used some of that money to purchase land to start the Flat Creek Road School, which was the first African American school in Black Mountain. He wanted all children to have access to a good education.”

The rock building constructed on the land began holding classes in 1886 and another school for Black children was later opened in the early 20th century. John Myra would serve as an honorary member of the local school board for 30 years before those institutions consolidated into George Washington Carver Elementary School in 1952, which Pertiller attended as a first- and second-grader before integration.

“It was so long ago, but I still remember sitting in Mrs. Pinkston’s class like it was yesterday,” Pertiller said of his time at the segregated school, which now operates as the Carver Community Center. “It was like a big family. We had amazing teachers and Mrs. Pinkston lived right down the street from me, so she would bring me to school with her.”

The building, which sits directly across the street from Oak Grove Cemetery, is just feet away from where John Myra is buried.

“He really laid a foundation for educational excellence,” Johnson said. “First, he set an example that you could follow your dreams if you had the gumption to do it, but then he made it a priority to improve the lives of the children who came after him. His impact on this community was tremendous.”

John Myra’s investment in education nearly 150 years ago continues to pay dividends today, according to Pertiller, who would go on to attend Cumberland College in Williamsburg, Kentucky and serve in the U.S. Air Force.

“Not only did he pass down a mentality that you work for what you get, and work hard,” Pertiller said. “But he also made sure that we had an opportunity to focus on education, and that's a powerful legacy by itself.”

A Legacy of Entrepreneurialism

“John Myra was a natural-born entrepreneur,” Lynch-Hudson said. “And according to elders, he possessed a pleasant and compassionate personality. You can see how John’s Myra’s traits have been inherently passed down in Archie, who has always had a pleasing demeanor, and also demonstrates our great-grandfather’s proficient people skills, necessary to excel as an entrepreneur.”

Before he was a free man, John Myra learned a wide range of skills performing his duties at one of the first hotels in eastern Buncombe County. As tourists began seeking respite in the mountains of Western North Carolina, Myra and her children toiled to support the growing industry.

John Myra, and many of his siblings, used the knowledge they acquired to earn a living once they were emancipated.

“Slavery here was still mostly focused on farming,” the museum director said. “But, the difference was that those farms were small, and often worked by one or two slaves, unlike the large plantations with hundreds of slaves that are commonly associated with the era.”

However, with the budding tourism industry in present-day Black Mountain, forced labor was often directed toward accommodating guests and maintenance of the facility.

“John Myra and his family played a significant role in building the tourism industry that we see here today,” Johnson said.

While the skills he acquired in his early life would help him find work, it was his business instincts and honesty that helped make John Myra successful, according to Lynch-Hudson.

“He became known as the first Black man of means in the Swannanoa Valley,” she said. “But, more importantly, he left Black Mountain a better place than he found it.”

Much of Pertiller’s professional career centered on helping others. He began his 23-year tenure at the Julian F. Keith Alcohol and Drug Abuse Treatment Center as a rehabilitation therapist in 1991. Sixteen years later he was promoted to a staff development position, and lhe would go on to serve as a member of the quality assurance committee for the North Carolina Intervention behavioral management program utilized by treatment facilities across the state. He retired as a state employee after four years at nearby Black Mountain Center.

In his post-retirement life, Pertiller set out on his own entrepreneurial path and helped develop an updated version of the behavior management program. He and his partners launched National Crisis Intervention Plus (NCI+) in 2017.

“There are over 400 instructors training people on our program in the state of N.C.,” he said. “We’re very proud of what we created and the work we do.”

A Legacy of Leadership

Archie Pertiller, Jr. takes the oath as a Black Mountain alderman, Dec. 14. Pertiller, who received the most votes in the history of the town where his great-grandfather, John Myra Stepp, was born into slavery. Photo by Fred McCormick

While the foundations of a couple of the 10 houses once owned by John Myra, including Pertiller’s childhood home, still stand, he likely wouldn’t recognize much of the community he called home for more than a century.

“He’d be shocked,” Pertiller said. “But, I know he would absolutely love seeing how his hard work influenced his descendants.”

John Myra’s great-grandson was emotional as he continued.

“He would be sad to see the places he remembered were long gone,” he said. “But he’d be pleased to see how this town has grown, and the success of his family.”

Change is inevitable, Pertiller added, underscoring the importance of the efforts of generations of the family to preserve the legacy of John Myra.

“I grew up on his land, and there are reminders of him all around me,” he said, motioning to a large tree that was on the property when his great-grandfather was alive. “Knowing everything that he sacrificed to help our family get where we are today has been something that’s helped motivate me for as long as I can remember.”

The leadership of John Myra was not only inspiring, it was almost tangible when Pertiller was growing up.

“I think of my father, who passed away two years ago, and all of the other strong men we all looked up to in our community,” he said. “My uncle, Winslow Whittington, Mr. Robert L. Stepp, Mr. William Hamilton, Mr. Bo Hamilton, Mr. Winfred Lynch, Mr. O.L. Sherrill are all men who were so powerful in Brookside and Cragmont. They were all hard-working men who played a tremendous role in our lives growing up, and some of them have a connection to John Myra somewhere down the line.”

As Pertiller stood proudly while being sworn in, he reflected on those who created the path that made the moment possible, and “it all ended with my great-grandpa,” he said.

“He was a gentleman born into slavery right here, and now one of his descendants is being sworn in on the town board,” Pertiller said. “I couldn’t have been there without John Myra Stepp, and I just hope he’s proud.”